I admit it. I failed to read my own campaign rules correctly. I was merrily into about 1534 without a care in the world, happily gobbling up more and more Burmese cities. Then I realised that I had misread the rules for cities resisting my invitation to become part of my kindly empire. If they drew a picture card, this did not count as 10 points against me, but as 10 PLUS another card. Resistance was going to grow, which is probably just as well otherwise the campaign would have got really boring.

So, back to 1531, and my empire was reduced to 3 cities plus Toungoo. I did receive an infantry base from the reserve, the one I lost against the raiders in the last turn, so my army was up to full strength. The first roll of the turn indicated that the random event was first this time, so I drew for it. Hm. ‘Vassal rebels with external aid’. A few dice rolls indicated that the rebel city was the newly conquered Prome. Clearly, they were unhappy about their new status within my gentle rule. They also had rather worryingly, Chinese allies.

I confess to having some fairly negative feelings in advance about this game. I think the problem is that my own Toungoo army does not have many in the way of elephants, and they are the Panzer divisions (for want of a batter expression) which mash up the enemy so the foot and cavalry can pick them off. At least, that is how I think the army should run, but experience is showing me something slightly different.

Still, the Prome army turned out to have 3 bases of elephants, 4 infantry, 2 bows, 1 artillery, and 2 cavalry, while the Chinese allies (only one contingent thankfully) had 1 cavalry, 1 bow and 1 infantry. The terrain I rolled up had a lot of hiding place for ambushes, as well, which was also a bit scary.

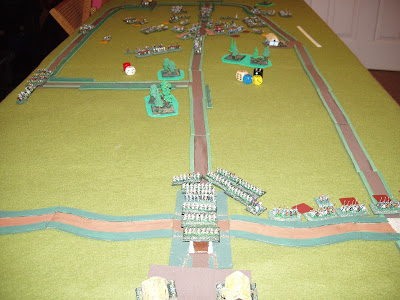

The terrain had a central hill, woods, two villages, a stream and some rough ground. The playing cards indicate possible ambushes. The enemy have deployed next to the hill, with their bowmen nearest the camera at the front. Their plan was to place the bows on the lower slopes of the hill to annoy my cavalry, while the elephants moved around my side of the hill to flank the foot or moved forward to crush the cavalry. Their cavalry, meanwhile, would outflank mine and roll it up.

My plan was to hold the left with the horse and hope that they could tie up the bows, elephants and cavalry, giving me a chance on the other flank. I had called in some allies – 3 infantry bases from Pegu, and so the plan was to use the infantry to smash through the centre, before any outflanking moves came to light. As a nod to sophisticated tactics, some of the infantry was to penetrate the woods on the far side and attempt to outflank the hill. As I said, I was rather nervous about this and expected a defeat.

The plans developed as outlined. On the far side, my infantry are moving forward, while the skirmishers have sprung the ambushes, revealing another cavalry base, a bows and another infantry in the village. The enemy bowmen are moving onto the hill, while the cavalry are getting around the rough going in the foreground. The elephants are getting into position and the artillery has opened fire on my brave troops.

Quite a lot of things happened in a fairly short space of time. My infantry moved into position as Prome’s deployed, and my cavalry deployed to face the enemy’s. Their elephants decided to ignore the cavalry and move towards the centre to threaten my foot. My only change was an all-out charge, but actually, the enemy got the drop with the foot, but they refused to move. Next turn, fortunately, I got the tempo and charged both horse and foot home. On the left of the shot (now taken from behind my lines) you can see the cavalry action is going in my favour, just about. In the centre, the leftmost infantry have routed their opponents, while the right-hand foot (with the general) have administered a bit of a pummelling to their foes. In their bound, the elephants desperately tried to make up ground to intervene in the infantry fight. It was still touch and go as my victorious foot would pursue their opponents, in disorder, and are hence elephant bait, especially as they would be hit in flank.

I was very, very, lucky. Enemy morale had slumped (on a bad roll) to ‘fall back’ which gained me some time. I won the next tempo roll, and my foot pursued the enemy, the routed bases of which burst through the line of archers, sweeping a base away. On the other side of the centre, my foot defeated their opponents and, pursuing, contacted the artillery base which was destroyed. I won two of the three cavalry combats on the left, which gave them another two routed bases. The end-of-turn morale roll was critical, and came out negative for them, which meant that the army routed.

Phew!

They lost 7 bases, and I did not lose any. But as I hope the narrative shows it was very close: the enemy elephants are within charge move of the flank of my disordered, pursuing infantry. That infantry would have been on a roll of 1+1d6 against 9+1d6 if the elephants had got home, let alone any damage done by the charge itself. Plus they would then have started to sweep away the rest of my infantry next to them. As my general was there as well, that would probably not have been survivable.

Even now I can feel the anxiety as I carefully measured distances in the centre, and whether my pursuing infantry would contact their artillery base (just), as well as carefully re-reading my ‘routers bursting through friendly troops’ rules. As noted above, I cannot guarantee I always read the stuff correctly, even if I wrote it.

Still, Prome is forced to re-submit to my rule, which might be a little less kindly than before. Perhaps I need to deport the population and sow the fields with salt, just to make a point, like the Romans did. Or maybe I am a bit more kindly than that. Maybe….